Pile Guide: silage surface and face management

When it comes to silages and drive-over pile building, Peter Robinson, a UC – Davis extension specialist, believes there is a preference for dairy producers to leave silage oversight to the custom operators who come in and build the piles.

“It’s like hiring somebody to come in and fix your toilet,” Robinson says. “Do you go and stand over the guy and say, ‘Well, I’m not quite sure you should be hooking it up that way?’ I don’t think so, right? So I think there’s a tendency for dairy owners to get a little disconnected from it. They don’t see silage management as something they need to get involved in and, in many cases, they should. They should get involved to the extent of making sure the basic principles are being followed by the operators who are building, covering and sealing the piles and also opening the piles later and removing plastic weekly.”

Underlay film

In the fall of 2013, Robinson led a research study in the northern San Joaquin Valley of California focusing on silage spoilage. The initial objective of Robinson’s study was to assess fermentation characteristics of corn silage in piles by measuring silage spoilage, as impacted by the use of thin plastic underlay films with or without enhanced oxygen barrier (EOB) characteristics.

“It was very evident by 2013 that putting a thin plastic underlay on the pile under the 5-millimeter (mil) black-on-white overlay really reduced surface spoilage,” Robinson says. “We didn’t need to do an experiment to prove this. The question was: Would the EOB plastic such as Silostop be further advantageous over the plain polymer polyethylene HiTec?”

The research showed there was no differences up to six months post-pile building in surface spoilage between the unopened piles covered with EOB plastic versus the polymer polyethylene plastic. “We looked at the differences in those large piles, and we could find no substantive difference in spoilage or fermentation characteristics. However, both films were highly effective,” Robinson says. According to Jim Ralles, U.S. HiTec representative, normal polyethylene underlay film (1.6 mil) currently costs about 3 cents per square foot, while EOB underlay film (1.8 mil) currently costs about 8 cents per square foot. This equates to $300 per 10,000 square feet versus $800 per 10,000 square feet.

Silage face

Despite the underlay films being very effective on closed piles, it did not explain why open piles had so much spoilage on the surface. So a year later he conducted a second experiment to examine silage surface, face periphery and deep mass spoilage during pile feedout as impacted by the underlay film. Results of this experiment made it clear to Robinson that the surface spoilage problems started to occur once the pile was opened.

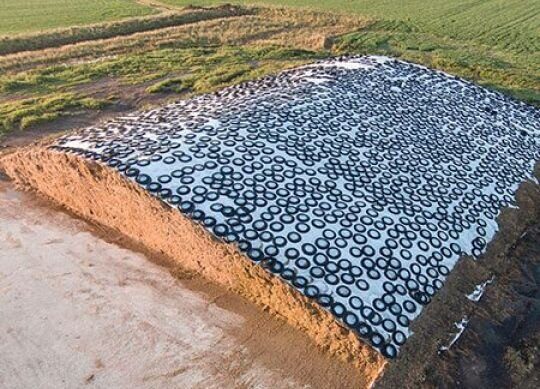

“Once a pile is opened, it doesn’t matter what kind of underlay plastic you’ve got on there because the air freely penetrates into the pile on the periphery. The air gets between the plastic and the silage at the face because the only thing that’s weighing the plastic down at that point are the tire lines,” Robinson says. “Any time it’s windy or even slightly breezy, the air is just coming right in between the plastic and the silage surface and can go a long way. In some cases, you can see the plastic moving up to 20 feet behind the exposed face, and of course that’s just an indication the air is reaching that far.”

This observation led Robinson to conduct a third experiment looking at the rate of penetration of molds and yeasts into the silage pile caused by air entry between the cut plastic and the silage surface.

“What we showed in this experiment is: The farther you go into the pile as you’re feeding it out, 10 to 12 inches a day on average in California, the penetration of molds and yeasts gets farther and farther from the exposed face,” Robinson says. “In other words, the rate that the spoilage is moving into the pile is faster than the rate that you’re removing silage.” A practical solution to this problem is to build piles that have an exposed face small enough to create a feedout rate of 28 to 34 inches per day. This can be achieved by building piles that are longer, narrower and not as high. However, due to limited concrete area, dairies are sometimes forced to build short, wide and tall piles that have slower feedout rates.

Rock lines

Robinson followed up with another study based on the idea to seal the exposed periphery of the pile by using a movable line of rock bags along the top of the exposed face to restrict the entry of air at the periphery. “However, those rock bags are a problem, and nobody likes to use them because they’re very heavy, awkward and can break open. In my opinion, they’re a pain because they need to be moved back weekly,” Robinson says. “What you’d really want is a tube made of a rubber compound that’s maybe 3 inches in diameter and could be rolled back from the exposed face. We looked for such a material in all kinds of industries but we never found one.”

However, Robinson feels a good area of use for the rock bags is around the outside of the pile at the ground to seal the plastic against the concrete because you don’t have to constantly move them and they’re there for a long period of time. The main reason to consider using rock bags around the outside of the pile at the ground is to avoid what is called the chimney effect. “If there’s any holes along the top of the pile or where the plastic overlays itself, on a sunny day the air will rise and pass out of the pile, and new oxygen-rich air will come in from an unsealed bottom. This is called the ‘chimney effect’ because it is just like air moving up in a chimney and the new air being sucked in at the bottom,” Robinson says. “However, if you’ve got weighted bags along the bottom, then the ability for new air to get in is reduced.”

Overall, Robinson’s advice for producers is to use a thin plastic underlay film, build piles with silage faces that are matched to silage need so pile feedout rate is 30 or more inches per day and install a rock line around the bottom of the pile at pile covering to minimize the chimney effect.

“The faster you can remove silage at feedout, the less of a problem you’re going to have with surface spoilage. The most common error producers in California make is: They don’t balance the rate of removal of silage from a silage face with the number of square feet of exposed face. They get too much exposed face for too little silage that is being removed daily,” Robinson says. “If you’re only moving a couple inches per day, then rock line bags are something you seriously need to look at. However, if you’re moving 2 feet or more per day, then the rock line advantages become much less because you’re moving the face back faster than the spoilage.”

Adapted from Audrey Schmitz for Progressive Dairy.